The Manuscript Average, Part 1

By Jesse Hurlbut

Last updated, December 15, 2013

When looking at medieval manuscripts, some easily gravitate to the ornamented and heavily illuminated pages for their spectacular visual quality. There is no question that the most well-known and widely reproduced images from the most famous manuscripts are usually the “pretty” pages. Serious scholarship provides important refinements to our understanding of these visual elements. Others capably focus on the text–sometimes a unique exemplar–that is inscribed on the pages. Where possible, they study the variations between different copies, comparing word for word. Still others are drawn to examine features of the codex or the paleography in all the minute details of composition and structure. These view the manuscript as an artifact capable of revealing much of its own history along with connections to other manuscripts or associated cultural phenomena.

In the course of my own explorations of medieval manuscripts (both hands-on and digitally), I have struggled to find an approach that allows for an overall appreciation of the entire object–to get a sense somehow for the whole thing. Already, the experience of hefting one of these historic volumes offers unique if vague satisfaction to the senses, even before opening it. One becomes aware of the weight, the dimensions, the wear and discoloration of the cover, the smell, and even the sounds it makes when the clasps are opened. The binding groans while the parchment crackles in response to the most careful gestures to leaf through it.

The Manuscript Average

Today, images of many thousands of manuscripts are available through digital repositories to casual and serious viewers. Without the physical presence of the actual volume between our hands, is there a way for us to take in some aspect of it all at once? For instance, what if we took all the pages of a given manuscript and overlaid them as if they were transparent?

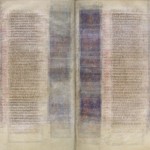

BNF Fr 138 (331 folios)

(Right-click and ‘View Image’ to enlarge images to full size)

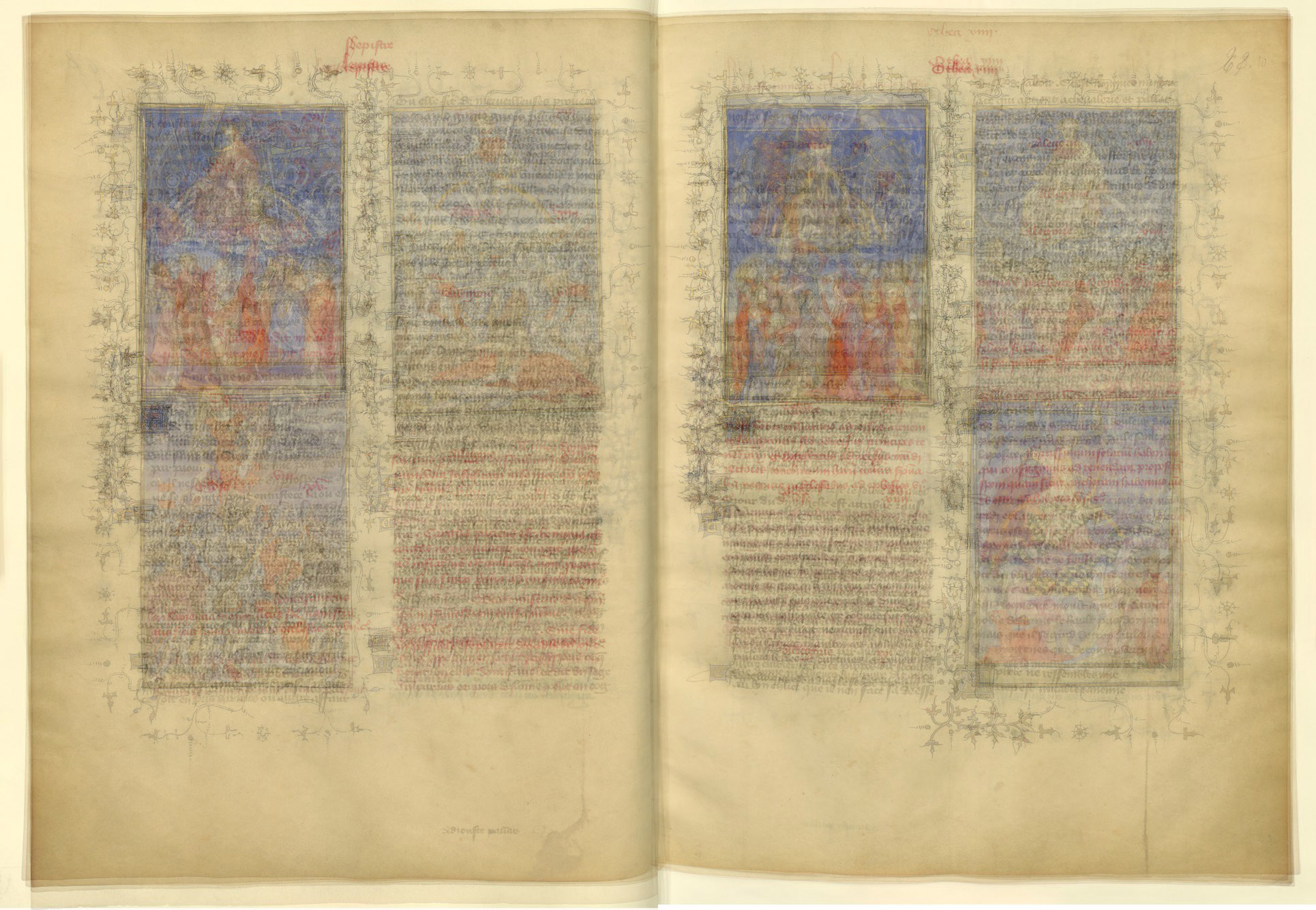

The above image looks like a poorly focused photograph of an opening in Guillaume Fillastre’s La Toison d’Or, but it is in fact all 331 folios digitally assembled into a single photograph–a visual average of all pages. What, if anything, can we see here? There is little evidence remaining of the 61 full-page illuminations, but we clearly make out the two-column text blocks along with some very regular marginal and inter-columnar decoration. Removing the full-page illuminations and the fully decorated borders from the average reduces the muddiness of the image somewhat.

Here is the average of the 35 folios that have full borders:

There are full-page illuminations on 22 versos and 39 rectos, which is why the average of the rectos is so much clearer.

When rectos and versos have been photographed individually, as in this copy of Jean de Vandenesse, Notes généalogiques sur la maison d’Autriche et journal des voyages de Charles-Quint, it is evident that the rectos and the versos need to be averaged separately because of the asymmetrical disposition of the text column. Image averages are different from hypothetical transparent parchment since only rectos are averaged with rectos, and versos with versos. A transparent support would reveal both rectos and versos on each side. Here we see, for example, the shadows of large capital letters in the left edge of the text block as designed by the creators of the manuscript. With transparent pages, the capitals would also bleed through on the right edge.

BNF Fr 5617 (325 folios)

In this detail from the above, we can make out overlapping ruling lines in the margins. The quality of the image average will depend on how well the source images align. Perfect alignment is unlikely, however, given the nature of parchment to shrink and warp, along with the difficulties of photographing an object that shifts position as one progresses from the front toward the back of the tome. For the purposes of an average, fairly close alignment such as we see here seems adequate.

This same manuscript (BNF Fr 5617) contains twenty-two pages of colorful heraldic blazons which disappear in the manuscript average. Rather than manually selecting the illustrated pages to perform a select average (as we did above), it is possible to automate the process with fairly good results. By mathematically comparing the mean color of each individual source image (red, green, blue, and overall) with the mean color of the manuscript average, it is possible to select only those images which have a darker mean color than the manuscript average. Below is an average of pages that are darker than the overall manuscript average. Curiously, far more versos are darker than the rectos.

In this detail of the darker-than-average folios, we make out the lines and colors of superposed coats of arms.

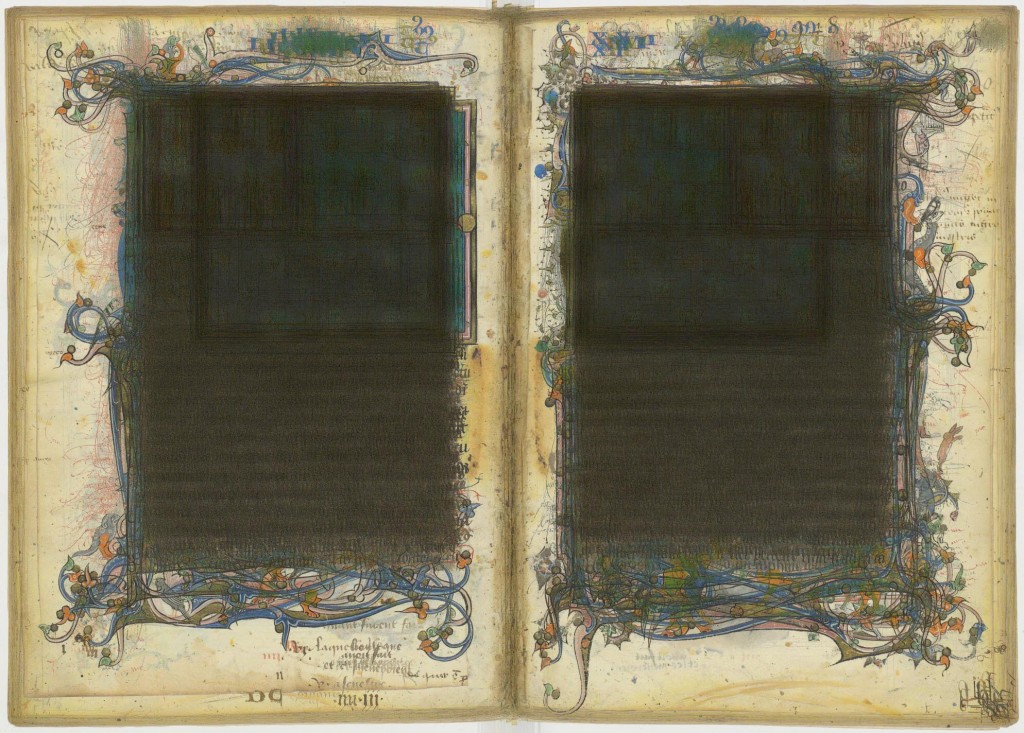

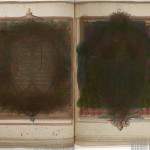

The more often a feature appears in the same position on a manuscript page, the more evident it will be in the image average. For example, the framed text in the Evangelia quattuor [Évangiles de Saint-Médard de Soissons] is extremely regular.

BNF Latin 8850 (222 folios)

Detail:

Some additional image enhancement emphasizes what is perhaps already clear enough. By digitally locating the edges in the average image and equalizing them, a map emerges, in which the darkest lines correspond to the most regular features.

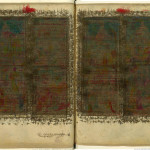

Another manuscript with systematic page layout throughout is the Bible moralisée. Each page of the entire volume is organized into the same grid of capitals, text blocks, and images.

BNF Fr 167 (321 folios)

In this detail, the alternating color of the capitals is discernible (gold with blue penwork on top, blue with red pen flourishes underneath), as is the frequent use of blue sky at the top of the miniatures

With edge enhancement and equalization, the layout of the entire manuscript becomes very apparent.

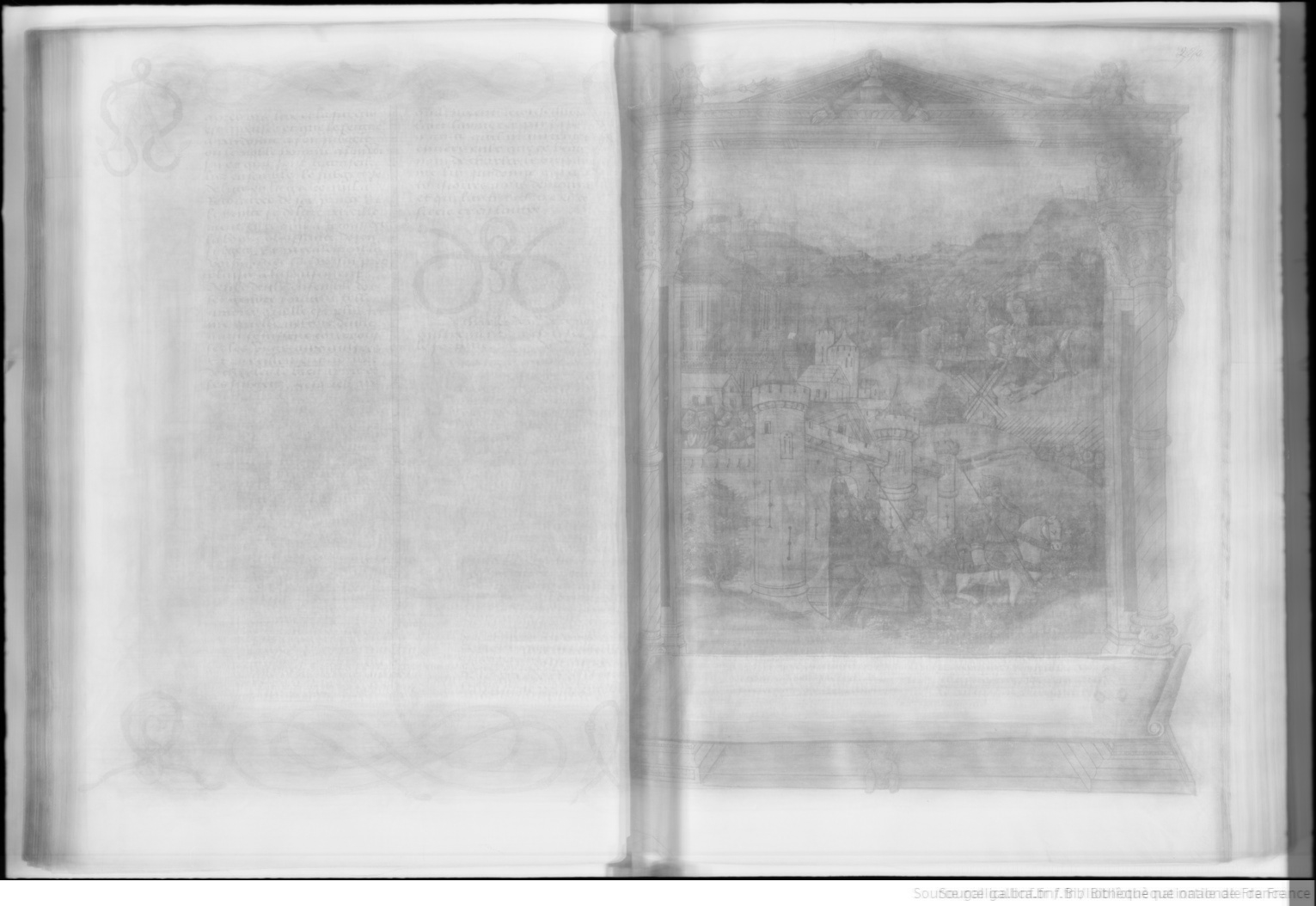

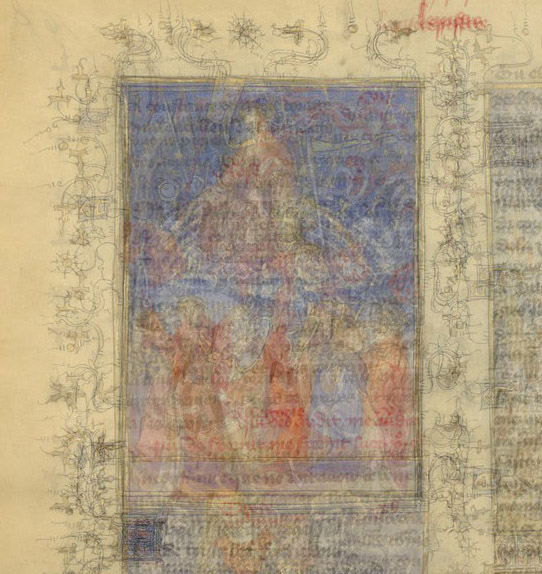

The image average for thinner volumes preserves more detail. This copy of Christine de Pisan, L’Epistre Othea, contains only 46 folios and shows clear evidence of illumination and marginal decorations.

BNF Fr 606 (46 folios)

Generating an average using fewer folios reveals many more details. This is an average of five folios starting on fol. 5v. The column-width miniatures are much more apparent in this average of a selection, as is the specific nature of the marginal decorations.

Many details from individual pages are also very visible, including some marginal vines that twist and turn following a regular template or pattern (above the miniature).

A final example will serve as a contrast to another technique discussed below. In this case, the manuscript (Nicolas de Nicolai, Traité du jeu des échecs) describes different strategies for the game of chess. As is obvious from the average image of 265 folios, there are more than half the pages which diagram the playing board.

The Darkest Pixel

If we take the same manuscript and process it differently, we arrive at another kind of overview of the document that reveals very different results. Instead of calculating the average color value of all folios as we did in all the previous examples, we apply here another technique that allows us to select the darkest color from all the folios at each pixel location to generate a whole new image. Here is the composite of the darkest pixels from the same treatise on chess. Notice that the chess board is no longer the most striking visual element, but the attractive marginalia, completely lost in the manuscript average, are visually significant here.

A similar attempt to generate an image based on the lightest pixels from the same stack of images returns essentially a blank sheet of parchment. The only distinguishable features are holes in the parchment that allowed the lighter backing sheet to be photographed and occasional bright streaks of yellow light where the camera captured the reflective surface of burnished gold leaf.

When summarized by the collection of darkest pixels, the 204 folios of Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry reveal a dark text block which suggests little more than consistently ruled text and the presence of regular capitals in the left edge of each column (the full bi-folio is visible in a link below). The stray images and decorations in the margin, however, leave thick traces of color, form and texture as seen in this detail of the gutter between the versos and the rectos.

Links to additional manuscript overviews (averages and darkest pixel) appear in the space below. Meanwhile, even though these blurry images lack the details necessary for art historians, literary scholars, or paleographers to perform their analyses, they do provide the means for attaining a casual and general appreciation for the digital medieval manuscript.

In addition to finding the Manuscript Average and the Darkest Pixel, there are still other approaches to a digitized general visualization of medieval manuscripts. This essay continues in The Manuscript Average, Part 2.

Manuscript Averages

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Darkest Pixels

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leave a Reply